Companies like Tesla are under increasing scrutiny to take responsibility for environmental and human rights violations along their supply chains. Global supply chains are complex and intertwined, but many eyes are focused on places like the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where raw minerals such as cobalt (critical for lithium-ion batteries) but also gold, tin, and coltan are sourced under often exploitative, polluting and violent conditions. In international relations, the concept of due diligence has become widely used as a tool for firms to meet their responsibility to respect human rights and the environment. But what exactly does due diligence mean? How does due diligence connect the responsibilities and rights of global consumers, companies, and mining communities? And what effects does it have in the DRC? In this contribution, we review the literature on the due diligence concept and analyze its effects on the ground in the DRC. Specifically, we highlight a shift in discourse from conflict-free sourcing to responsible sourcing and reflect on what this might mean for small-scale miners and mining communities in the DRC.

Due diligence

Tesla recognizes the importance of mining to local communities and encourages ethical sourcing from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). As recommended by the OECD, we do not support an embargo, implicit or explicit, of any DRC material, but instead, allow sourcing from the region when it can be done in a responsible manner through audited value chains (Tesla).

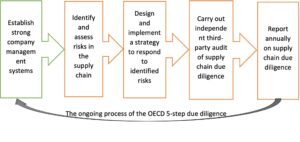

Due Diligence has become a well-entrenched practice in mineral supply chains, a tool for identifying, assessing, and acting upon risks. Risks are nowadays broadly understood to include forced labour, child labour, human rights violations, and war crimes (OECD, 2016). Supply chain actors are responsible for carrying out their own due diligence. To do so, they can use practical guidelines, due diligence and traceability programmes, and certification schemes that help firms comply with standards (Postma and Geenen, 2020). The most widely used guidance is the OECD Due Diligence Guidance (3rd edition in 2016), which recommends a five-step framework for doing due diligence (figure 1). In collaboration with the OECD, the China Chamber of Commerce of Metals, Minerals & Chemical Importers and Exporters (CCCMC) also developed Due Diligence Guidelines in 2015. Well-known due diligence and traceability programmes are the International Tin Supply Chain Initiative (ITSCI) or Better Mining, both operational in the DRC. Notable certification programmes include the Regional Certification Mechanism of the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region, the Chain-of-Custody Standard of the Responsible Jewellery Council, and the Responsible Minerals Assurance Process of the Responsible Minerals Initiative (Postma and Geenen, 2020).

Apart from these voluntary guidelines, mandatory requirements for mineral sourcing companies have been included in American and European legislation. In its Section 1502, adopted in 2010, the US Dodd-Frank Act requires listed companies to report on whether or not the minerals they imported from the DRC or its neighbouring countries have been tainted by conflict (SEC, 2012). While earlier legislation was narrowly focused on conflict financing in the DRC, following alarming reports about ongoing violence in the early 2000s, more recent initiatives take a broader scope. On 17 May 2017, the European Parliament and Council adopted a new import framework on “Conflict Minerals” under Regulation 2017/821. Coming into effect in 2021, this first mandatory regulation for European Union (EU)-based companies importing the 3TG (tin, tantalum, tungsten, and gold) set up a “responsible importer” scheme in order to stop (1) conflict minerals and associated metals from being exported to the EU; (2) global and EU smelters and refiners from using these minerals, and (3) artisanal miners from being abused. On the one hand, the regulation may be criticized for not going far enough in requiring that only importers, not end-user companies, report. Simultaneously, it has been praised for going further than Dodd-Frank in its geographical scope – from DRC and neighbours to all conflict-affected and high-risk areas – and its developmental approach – foreseeing accompanying measures to help Congolese producers comply. The regulation is also seen as a “trial run” for a more comprehensive EU Due Diligence legislation.

In February 2022 the EU Commission published a proposal for a directive on corporate sustainability due diligence (CSDD), which presents itself as a key entry point for the development of “more inclusive and holistic” policies for a due diligence framework in natural resource management. If the directive gets approved, EU member states will have to domesticate it into national law. However, in December 2022 the EU ministers agreed on some proposed changes, which, as noted by some advocacy NGOs, “significantly watered down the already flawed proposal from the European Commission”. One of the proposals is to replace the value chain with a “chain of activities”, which covers only a small part of downstream activities.

Critical voices have expressed concern, however, about both the process of due diligence, and its ability to effectively reduce human rights violations and conflict. First of all, there is a risk of what Landau (2019) has called “cosmetic compliance”. This means that companies may be fully compliant with due diligence requirements by adopting all necessary “internal policies and compliance structures”, while there are no actual changes in their supply chain. In other words, they may identify risks and set up strategies to mitigate them, but if the audit process shows no real change on the ground, there are no sanctioning mechanisms (see Postma and Geenen, 2020). Second, by making supply chain actors monitor each other, regulation is being outsourced to private actors. According to Sarfaty (2015), this raises accountability concerns. Responsibilities and costs for doing due diligence are also shifted down the supply chain, from downstream to upstream actors. Doing due diligence is particularly difficult for small-and medium sized enterprises, which have been excluded from legal frameworks (Verbrugge et al., 2022).

Due diligence in the DRC

As mentioned earlier, concerns about conflict financing in the DRC gave rise to both mandatory and voluntary due diligence initiatives around 2010. These early initiatives focused on the East of the country, specifically the provinces of Maniema, North Kivu and South Kivu, where tantalum, tin, tungsten and gold are mined (3TG). Concomitant with the adoption of Dodd-Frank Section 1502, then-president Kabila imposed a six month ban on artisanal and small scale mining in the three provinces. After the ban was lifted, a de facto ban persisted, with devastating consequences for local livelihoods. While Parker et al. (2016) documented a rise in child mortality as a consequence of reduced health access and consumption, Stoop et al. (2018) found that violence was not reduced, but merely shifted. Authors such as Vogel et al. (2016), Wakenge et al. (2018), and Cuvelier et al. (2014) demonstrated that the implementation of traceability and due diligence programmes resulted in monopolies and depressed the prices received by small-scale miners.

Due diligence programmes currently active in DRC include the abovementioned ITSCI and Better Mining programmes. Certification programmes include the Certified Trading Chains initiatives by the German government and the Congolese government Initiative for the Traceability of Artisanally Mined Gold (ITOA). There are also many responsible sourcing and community initiatives that target 3T (Madini kwa Amani na Maendeleo, Solutions for Hope, etc.) gold (Peace Gold project, Just Gold, Zahabu Safi, Women of Peace, etc) and cobalt (Her Security, Cobalt for Development, Mutoshi Pilot Project, etc.). Finally, there are a number of monitoring and reporting initiatives, such as Kufatilia and Matokeo. A recent IPIS study concluded that the positive effect of due diligence on human rights compliance is still unclear. Although there seems to be a correlation between the presence of due diligence programmes and reduced conflict and positive livelihood outcomes, the report questions whether there is a causal relationship at work. There is very probably bias as due diligence programmes are usually established in mines with relative security and accessibility. In other words, and as mentioned before, it is still unclear whether due diligence can really achieve its intended effects.

In the DRC, three additional concerns are worth mentioning. First, the risk of a de facto ban is still present, as for companies it has become much more costly and burdensome to source from the region (Manhart and Schleicher, 2013). This risk is lower, however, for cobalt, where the DRC is the major worldwide supplier. Second, due diligence has become a major business activity and a market in itself, where consulting firms and auditors make a lot of money, while relatively little money is directed to the most affected mining communities. Third, on a broader level, these dynamics also highlight a problematic “white saviourism” complex and the perpetuation of neo-colonial dynamics, as recently documented in Christoph Vogel’s (2022) book.

From conflict-free to responsible sourcing

The changing global context as well as the critiques of previous due diligence efforts, as described above, have resulted in several shifts in the character of contemporary due diligence efforts. In this section we identify these general shifts, as well as how they play out in the case of the DRC. The complexity of contemporary global supply chains has led to a so-called governance gap in international relations, where the boundaries between public and private activities have become blurred. Whereas previously corporate actors were mainly viewed as economic actors, they are now increasingly viewed as political actors with societal roles and responsibilities (Scherer and Palazzo, 2011, Miklian and Schouten, 2014). Partzsch and Vlaskamp (2016) have coined this the foreign accountability norm, which entails that companies are being held accountable for harmful activities abroad.

The emerging foreign accountability norm also results from previous experience. For instance, the devastating impact of the de facto embargo after Dodd-Frank has led to an increased emphasis on engagement with actors in conflict-affected and high risk areas as a crucial aspect of due diligence efforts. Whereas previously corporate actors were focused on sourcing conflict-free, we now see a trend towards “responsible sourcing”, where active engagement with local communities is assumed to lead to positive effects on the ground. One example of this is the commitment expressed by Tesla to source “in a responsible manner” from the region. On a more pragmatic, and perhaps cynical note, a de facto embargo is not really an option for the case of cobalt, where 70% of global supplies come from DRC. Therefore, engagement does not only seem a moral choice, but also an inevitable and market-driven one.

We can identify this shift from sourcing conflict-free to sourcing responsibly in both the content and the form of due diligence efforts affecting the DRC. First, with regard to the form, due diligence efforts are becoming more diverse in terms of involved actors. For example, a range of multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs) are emerging as a form of public-private governance built on the shared assumption that cooperation amongst various stakeholders is the key to a responsible supply chain. Industry actors are collaborating with governments and civil society organizations in addressing and mitigating environmental and human rights violations. Examples of MSIs active in the DRC include the Public-Private Alliance for Responsible Minerals Trade (PPA), the Responsible Minerals Initiative (RMI), the Global Battery Alliance (GBA), and the Fair Cobalt Alliance (FCA). Second, as mentioned above, more mandatory due diligence efforts are emerging as well (Deberdt and Le Billon, 2021). Rather than being contradictory, Baumann-Pauly and Trabelsi (2021) argue, voluntary and mandatory due diligence can complement each other.

With regard to the content, in keeping with the participatory turn in the field of development in general, participation has become a focal point of due diligence (Macdonald, 2017: 594). This concept ranges from stakeholder participation – hence the increase of MSIs – to civil society participation and rights holders’ participation. In mineral supply chain regulation, this is evident in the increased attention to integrating the artisanal small-scale mining (ASM) sector – whose informality has often been associated with human rights violations – into these efforts. Most responsible sourcing discourses emphasize the formalization of ASM as key to ensuring a responsible supply chain and as a prerequisite for effective due diligence (Singo and Seguin, 2018: 8). Furthermore, we can also identify a shift in the mineral scope of due diligence efforts. In the context of the green energy transition, the demand for so-called battery minerals has risen significantly. In the DRC, home to around 70% of the global cobalt reserves, this cobalt boom has prompted a range of initiatives and efforts specifically focused on cobalt due diligence (Deberdt and Le Billon, 2021: 3, 11). This is reflected in the OECD Guidance, which in its first edition (2011) focused on 3TG, but later (2016) extended its scope to all relevant minerals. Copper and cobalt were explicitly included through an additional report published in 2019. As the mineral scope is broadening, the understanding of risks and associated areas of risk has been broadened too, from conflict financing to a vast range of environmental, human rights related and labour risks.

While there is a trend towards broadening the scope and seeking to limit the adverse consequences of earlier supply chain regulation, there are still a number of critical assessments to be made. For example, multi-stakeholder initiatives have proven to be of limited success in addressing human rights concerns, and tend to prioritize corporate interests, thereby reinforcing instead of changing historical power structures. Similar critiques have been raised regarding the emphasis on participation. When participation is designed and implemented in a top-down manner, it can also reinforce power imbalances. Statements around participation as a part of a responsible sourcing discourse do not automatically translate into meaningful participation of rights holders (Macdonald, 2017: 595). As these critiques show us, there is often still a gap between the rhetoric and reality of due diligence efforts. Furthermore, the case of the DRC illustrates that due diligence, if confined to a technical check-the-box exercise, risks having few or even negative effects. Fortunately, lessons have been learned from previous efforts, and discourses and practices are constantly evolving. On the other hand, the “due diligence industry” often seems to be very much self-seeking. It is sustaining a world of consultants, due diligence programmes, and auditors, and producing an endless amount of risk assessments, monitoring, and CSDD reports, while it remains difficult to scale up from successful pilot projects and engender real, structural change.

Concluding remarks

Due diligence has become a cornerstone of global supply chain regulation. Since its emergence in mineral supply chains, practices have shifted from voluntary to mandatory, from conflict risks to broader human rights and labour risks, and from conflict-free sourcing to responsible sourcing and engagement. With its reputation as one of the worst examples of mining-related conflicts, human rights violations, and labour exploitation, the DRC seems to be a laboratory for due diligence initiatives. Yet academic research has shown that their effects have been unclear at best, and adverse at worst. More often than not, international discourses seem to be disconnected from realities on the ground. Affected communities are seldom consulted, let alone able to actively participate, in the design of due diligence programmes. Assessments regarding what constitutes a supply chain “risk” are made at decision-making levels that they cannot access. Some initiatives are now explicitly engaging with affected communities to address this power imbalance. Our research project at the University of Antwerp, “Driving Change”, will look into this in the next three years, based on field research in DRC’s South Kivu and Lualaba provinces. We will seek ways to meaningfully include small-scale miners, mining communities, cooperatives, and unions in ethical supply chain initiatives. The end result should be a mineral supply chain in which ethical decisions are driven by the people who are most affected by negative externalities.

Figure 1: Source: OECD, 2016.

Source: E International