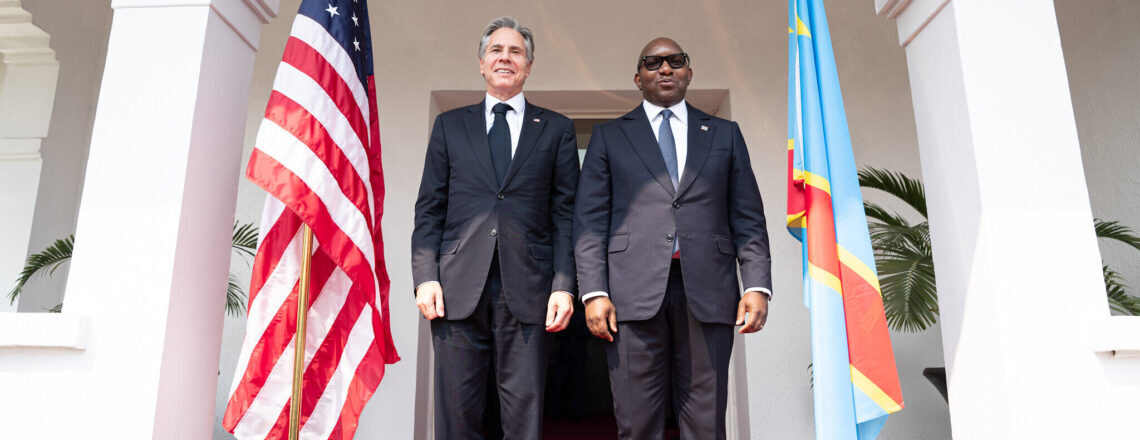

US State Dept. Starts Building New Embassy in Kinshasa, DRC

As a demonstration of the enduring commitment to strengthening the relationship between the United States and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), U.S. Ambassador to the DRC Lucy Tamlyn, with representatives from the U.S. Mission to the DRC, the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Overseas Buildings Operations (OBO), and Congolese officials, celebrated the groundbreaking of the new U.S. Embassy in Kinshasa on August 29.

The embassy will be a symbol of our shared commitment to advancing democratic values, sustainable economic growth, and global cooperation.

The project is expected to infuse $170 million into the local economy and provide employment opportunities for more than 1,600 Congolese nationals. Since April 2023, the United States has invested $1.4 million in the local economy to advance this project and expects to procure cement, concrete aggregates, soils and fill materials, and landscaping materials locally. Congolese construction workers will also benefit from skills acquired as part of the project and related safety training.

The embassy design draws inspiration from the diverse environmental mosaic of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Department is committed to implementing rigorous energy-saving and sustainability strategies to minimize the environmental impact of construction, optimize building performance, and enhance sustainability and resilience.

SHoP Architects of New York, New York, is the design architect, and B.L. Harbert International of Birmingham, Alabama, is the design-build contractor, with Page of Washington, D.C., as the architect of record.

Since the start of the Department’s Capital Security Construction Program in 1999, OBO has completed 177 new diplomatic facilities, and currently has more than 50 active projects in design or under construction worldwide.

OBO provides safe, secure, functional, and resilient facilities that represent the U.S. government to host nations and that support U.S. diplomats in advancing U.S. foreign policy objectives abroad.

Source: Mirage News